Valuation 101

How to Value Stocks Like a Professional

Valuation is important.

Even the best company in the world can be a horrible investment if you pay too much.

Let’s teach you how to value a company like a professional today.

Like any other investor, one of the first books I read was The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham.

Benjamin Graham is the father of value investing and provided plenty of valuable lessons.

One of the most important ones?

"Price is what you pay, value is what you get."And guess what? He is 100% correct.

It’s all about the Fundamentals (and Valuation)

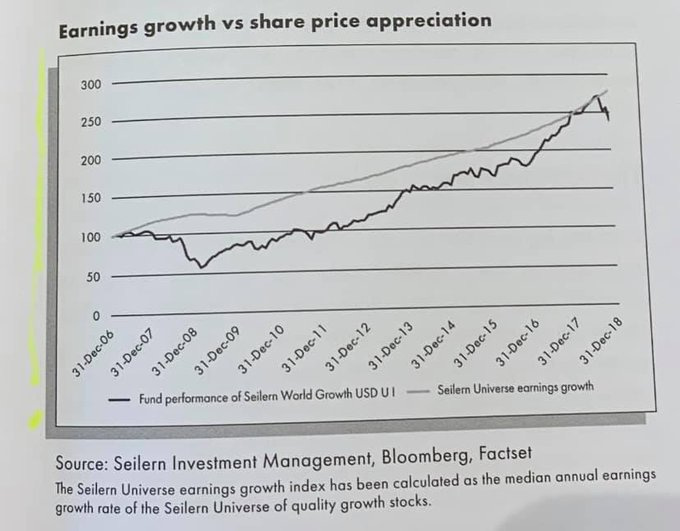

Here’s how some companies were valued five years ago and how their stock price has evolved since then:

Isn’t that strange?

Despite very high valuation multiples, these quality businesses kept outperforming.

And this while cheap stocks like Verizon and Intel kept getting cheaper.

It looks like Buffett was right, once again:

As a teenager, I was a value investor myself.

After some expensive lessons, I learned the hard way that cheap junk can always get cheaper.

Why? In the end, stock prices will always follow the evolution of the intrinsic value.

Deep value investors might be surprised by this.

Don’t get me wrong... Valuation is still very important to me.

It’s an essential piece of the investment puzzle.

You don’t believe me?

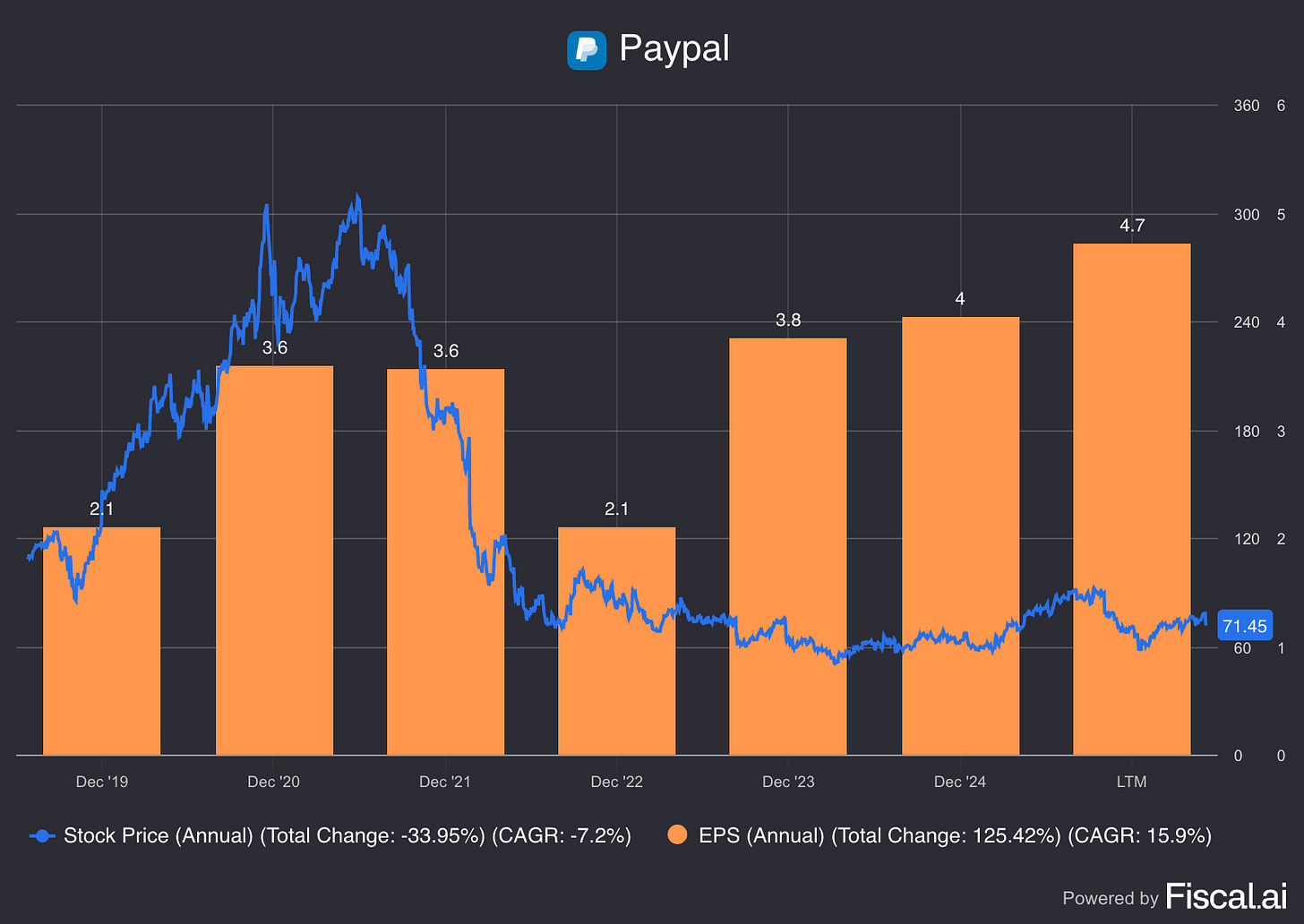

Over the last 5 years, the intrinsic value of PayPal doubled.

Over the same period, PayPal investors lost 28.7%. That’s the power of valuation at work.

There are plenty of similar examples like this one.

If you bought Microsoft in January 2000, you had to wait 16 years to make a profit!

January 2000 was just before the burst of the Dotcom Bubble, and also the last month Bill Gates was the CEO.

Are you looking for great investments? Use this as a rule of thumb:

High Price + Bad Business = A recipe for disaster

Low Price + Bad Business = A road to nowhere

High Price + Good Business = Mixed feelings

Low Price + Good Business = The golden eggThe lessons?

Fundamentals beat valuation in the long run (Nvidia versus Intel)

That’s not the same as saying that valuation doesn’t matter (PayPal and Microsoft)

The P/E ratio is a weak metric

Let’s elaborate on these topics.

Fundamentals beat valuation

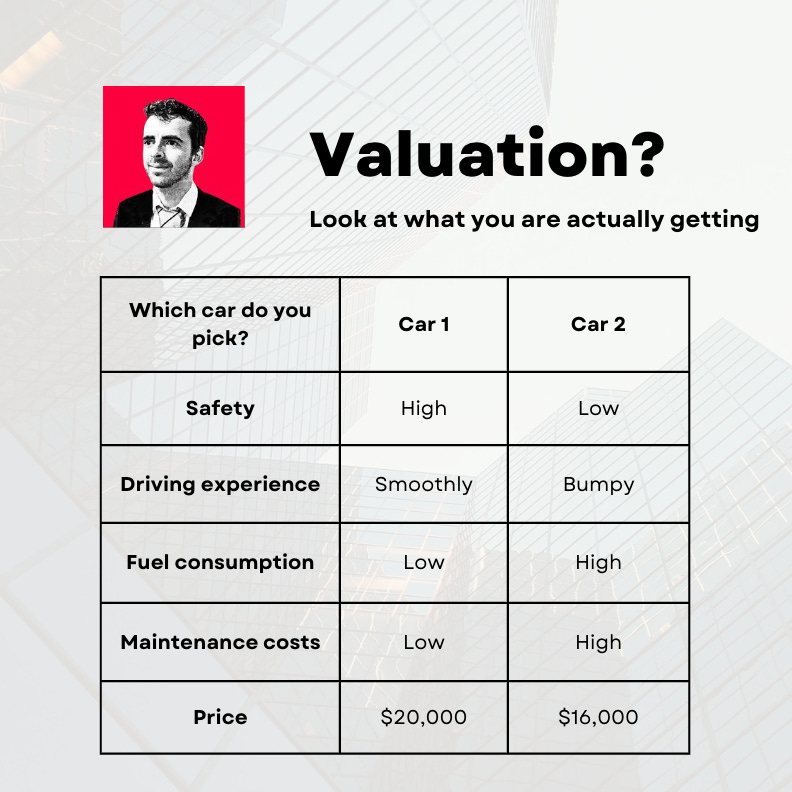

Let’s translate the stock market into your daily life.

You had a car accident last week. The car was declared a total loss. Luckily, your insurance will pay you back all the money.

Now, you are facing an important decision: you need to buy a new car.

You have two options:

Despite the higher price, the obvious choice is to go for car 1.

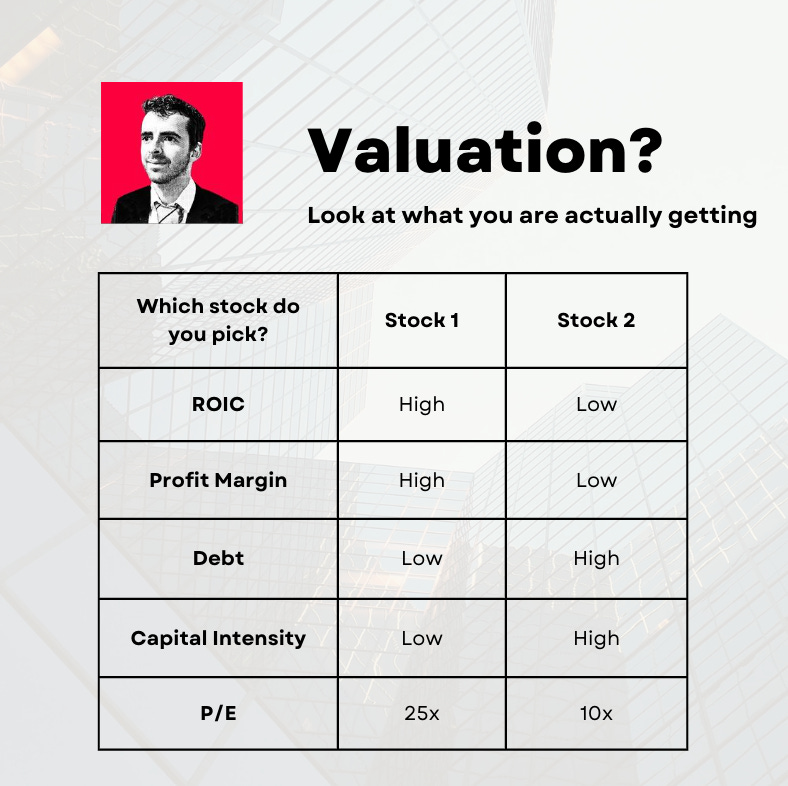

Let’s leave your daily life behind and return to the stock market.

Now, instead of two cars, there are two stocks.

A stock trading at a P/E of just 10x looks tempting, right?

However, stock picking is not very different from buying a new car or doing your groceries.

The price doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Price only makes sense if you compare it to what you are receiving in return.

A low price can be nice. But you make the most money by buying great companies and holding them for a long time.

"If you bought the S&P 500 at a P/E of 5.3x in 1917 and sold it in 1999 at a P/E of 34x, your annual return would have been 11.6%. Only 2.3% p.a. came from the massive increase in P/E. The rest of your return came from the companies’ earnings and reinvestments." - Terry SmithJust like car 1 was worth its price, it makes a lot of sense to pay up for quality on the stock market.

But there are two important nuances:

You need to be right on the business

Even if you are right on the business, not any price is justifiable

"Even the best businesses in the world can be a bad investment if you pay too much." - Warren BuffettThe P/E ratio is a weak metric

The P/E ratio shows how many years it takes to earn back the money you paid for a stock.

Sounds complicated? Let me explain.

A P/E of 20 means the company needs 20 years to earn back your money. But that's just in theory.

In reality, the P/E ratio doesn’t tell the whole story. It ignores growth, management quality, and industry challenges.

It simply shows how much investors are willing to pay for earnings. A low P/E isn’t always a good deal, and the other way around.

Value isn’t just paying a low P/E, it’s getting more than you pay for.

"A low P/E ratio doesn't always mean a stock is cheap, and a high P/E ratio doesn't always mean a stock is expensive. The ratio only tells you part of the story." - Peter LynchThat’s exactly why we use other valuation methods, like the Earnings Growth Model and the Reverse DCF.

Earnings Growth Model

I wrote a full article on this wonderful valuation tool.

In short, it shows the yearly return you can expect on your investment.

If you’re interested in learning more, click here.

Reverse DCF

Charlie Munger once said that to solve a complex problem, invert, always invert. Turn a situation or problem upside down

That’s exactly what a Reverse DCF does.

Instead of guessing what a company might be worth, we let the market speak. We don’t start with our assumptions. Instead, we analyze the assumptions already baked into the stock price.

Then, we ask ourselves: Do these expectations make sense? If they seem too pessimistic, that’s where the opportunity lies.

A good investor doesn’t need a complex DCF to see if a stock is interesting.

Keep it simple.

"If you need Excel to see if a stock is valued attractively, it's probably not." - Mohnish PabraiJust like the Earnings Growth Model, I wrote a full article about this topic. You can read it here.

Portfolio

Finally, here is the under- and overvaluation of every company in Our Portfolio:

![It's better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price" - Warren Buffett [800x362] : r/QuotesPorn It's better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price" - Warren Buffett [800x362] : r/QuotesPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!tFn4!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1230379a-b190-4f41-acdc-83f9dd16ed57_640x289.png)